Table of Contents

MCQ 1

- C40 is the first of its kind summit being organised for the first time in Copenhagen

- It is an initiative of UN Habitat

Choose correct

(A) Only 1

(B) Only 2

(C) Both

(D) None

- The C40 World Mayors Summit is C40’s milestone event, serving as a unique forum for member cities to present the innovative actions they have taken to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and improve climate resilience; influence decision makers – from fellow mayors to CEOs and national leaders – to take the bold and urgent action needed to keep global temperature rise to below 1.5 °C; and inspire participants and citizens to take climate action in their own lives.

- Over the past decade, C40 has convened six Mayors Summits, hosted by London (2005), New York (2007), Seoul (2009), Sao Paulo (2011), Johannesburg (2014) and Mexico City (2016). Each C40 Mayors Summit has provided unique opportunities for the mayors of the world’s great cities to showcase their climate leadership on the global stage.

- With its agenda setting programme, and inspiring set of speakers, the C40 Mayors Summit is a unique global event. Previous C40 Summits have made headlines around the world by publishing groundbreaking research, showcasing cutting edge innovation from cities and launching new partnerships to promote creative urban solutions to climate change.

- Copenhagen is a true pioneer in creating the sustainable, healthy and liveable cities of the future. The C40 World Mayors Summit in Copenhagen will be the first to truly bring the citizens of the city into the Summit.

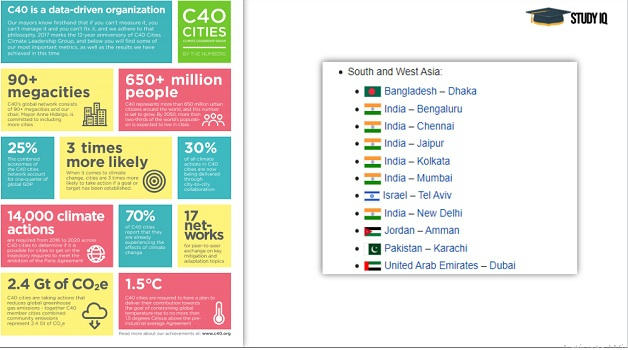

- C40 is a network of the world’s megacities committed to addressing climate change. C40 supports cities to collaborate effectively, share knowledge and drive meaningful, measurable and sustainable action on climate change.

- C40 Cities connects more than 90 of the world’s leading cities to take bold climate action and build a healthier and more sustainable future. Representing 700+ million citizens and one quarter of the global economy, mayors of C40 cities are committed to delivering on the most ambitious goals of the Paris Agreement at the local level, as well as to cleaning the air we breathe.

- The C40 World Mayors Summit will feature innovative events, plenary sessions, breakout sessions, press conferences and cultural activities. While C40 originally targeted megacities for their greater capacity to address climate change, C40 now offers three types of membership categories to reflect the diversity of cities taking action to address climate change. The categories consider such characteristics as population size, economic output, environmental leadership, and the length of a city’s membership.

- Megacities

- Population: City population of 3 million or more, and/or metropolitan area population of 10 million or more, either currently or projected for 2025. OR GDP: One of the top 25 global cities, ranked by current GDP output, at purchasing-power parity (PPP), either currently or projected for 2025.

- Innovator Cities

- Cities that do not qualify as Megacities but have shown clear leadership in environmental and climate change work. An Innovator City must be internationally recognized for barrier-breaking climate work, a leader in the field of environmental sustainability, and a regionally recognized “anchor city” for the relevant metropolitan area.

- Observer Cities

- A short-term category for new cities applying to join the C40 for the first time; all cities applying for Megacity or Innovator membership will initially be admitted as Observers until they meet C40’s year-one participation requirements, for up to one year. A longer-term category for cities that meet Megacity or Innovator City guidelines and participation requirements, but for local regulatory or procedural reasons, are unable to approve participation as a Megacity or Innovator City expeditiously.

- The United Nations Human Settlements Programme (UN-Habitat) is the United Nations programme for human settlements and sustainable urban development.

- It was established in 1978 as an outcome of the First UN Conference on Human Settlements and Sustainable Urban Development (Habitat I) held in Vancouver, Canada, in 1976. UN-Habitat maintains its headquarters at the United Nations Office at Nairobi, Kenya.

- It is mandated by the United Nations General Assembly to promote socially and environmentally sustainable towns and cities with the goal of providing adequate shelter for all. It is a member of the United Nations Development Group.

- The mandate of UN-Habitat derives from the Habitat Agenda, adopted by the United Nations Conference on Human Settlements (Habitat II) in Istanbul, Turkey, in 1996. The twin goals of the Habitat Agenda are adequate shelter for all and the development of sustainable human settlements in an urbanizing world.

- Since January 2019 the Executive Director is Maimunah Mohd Sharif, who had served as the Mayor of Penang Island prior to her appointment in UN-Habitat by the Secretary-General of the United Nations, António Guterres. The current Deputy Executive Director is Victor Kisob of Cameroon who was appointed by António Guterres in July 2018

- The conferment of a person, as a citizen of India, is governed by Articles 5 to 11 (Part II) of the Constitution of India. The legislation related to this matter is the Citizenship Act 1955, which has been amended by the Citizenship (Amendment) Acts of 1986, 1992, 2003, 2005, and 2015

Citizenship by naturalization

- Citizenship of India by naturalization can be acquired by a foreigner who is ordinarily resident in India for 12 years (throughout the period of 12 months immediately preceding the date of application and for 11 years in the aggregate of 14 years preceding the 12 months) and other qualifications as specified in Section 6 (1) of the Citizen Act,1955

Citizenship Amendment Bill 2016

- The Indian Citizenship Amendment Bill was proposed in Lok Sabha on July 19, 2016, amending the Citizenship Act of 1955.

- If this Bill is passed in Parliament, illegal migrants from minority communities like Hindu, Sikh, Buddhist, Jain, Parsi or Christian coming from Afghanistan, Bangladesh, and Pakistan will then be eligible for Indian citizenship but excluding Muslim community.

- The Bill relaxes the 11 year requirement of residing in India to 6 years for the above migrants to India

- The Hindu-Kush-Himalayan (HKH) region is considered the Third Pole [after the North and South Poles], and has significant implications for climate

- The HKH region spans Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, China, India, Kyrgyzstan, Mongolia, Myanmar, Nepal, Pakistan, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan.

- the India Meteorological Department (IMD) will collaborate with meteorological agencies in China and Pakistan, among others, to provide climate forecast services to countries in the region.

- Most criticisms of modern agricultural practices are criticisms of post-Liebig developments in agricultural science. It was after the pioneering work of Justus von Liebig and Friedrich Wöhler in organic chemistry in the 19th century that chemical fertilizers began to be used in agriculture. In the 20th century, the criticisms levelled against Green Revolution technologies were criticisms of the increasing “chemicalisation” of agriculture.

- Claims were made that alternative, non-chemical agricultures were possible. Organic farming became an umbrella term that represented a variety of non-chemical and less-chemical oriented methods of farming. Rudolf Steiner’s biodynamics, Masanobu Fukuoka’s one-straw revolution and Madagascar’s System of Rice Intensification (SRI) were examples of specific alternatives proposed.

- In India, such alternatives and their variants included, among others, homoeo-farming, Vedic farming, Natu-eco farming, Agnihotra farming and Amrutpani farming. Zero Budget Natural Farming (ZBNF), popularised by Subhash Palekar, is the most recent entry into this group.

- According to Mr. Palekar, all knowledge created by agricultural universities is false. He calls Liebig as “Mr. Lie Big”. He labels chemical fertilizers and pesticides as “demonic substances”, cross-bred cows as “demonic species” and biotechnology and tractors as “demonic technologies”. At the same time, Mr. Palekar is also critical of organic farming. For him, “organic farming” is “more dangerous than chemical farming”, and “worse than [an] atom bomb”.

- He calls vermicomposting a “scandal” and Eiseniafoetida, the red worm used to make vermicompost, as the “destructor beast”. He also calls Steiner’s biodynamic farming “bio-dynamite farming”. His own alternative of ZBNF is, thus, posed against both inorganic farming and organic farming.

- Mr. Palekar’s premise is that soil has all the nutrients plants need. To make these nutrients available to plants, we need the intermediation of microorganisms. For this, he recommends the “four wheels of ZBNF”: Bijamrit, Jivamrit, Mulching and Waaphasa. Bijamrit is the microbial coating of seeds with formulations of cow urine and cow dung. Jivamrit is the enhancement of soil microbes using an inoculum of cow dung, cow urine, and jaggery. Mulching is the covering of soil with crops or crop residues. Waaphasa is the building up of soil humus to increase soil aeration.

- In addition, ZBNF includes three methods of insect and pest management: Agniastra, Brahmastra and Neemastra (all different preparations using cow urine, cow dung, tobacco, fruits, green chilli, garlic and neem).

Unsubstantiated claims

- To begin with, ZBNF is hardly zero budget. Many ingredients of Mr. Palekar’s formulations have to be purchased. These apart, wages of hired labour, imputed value of family labour, imputed rent over owned land, costs of maintaining cows and paid-out costs on electricity and pump sets are all costs that ZBNF proponents conveniently ignore.

- Second, there are no independent studies to validate the claims that ZBNF plots have a higher yield than non-ZBNF plots.

- The Government of Andhra Pradesh has a report, but it appears to be a selfappraisal by the implementing agency; independent studies based on field trials are not available.

- There is a report from the La Via Campesina for Karnataka, but it is based on accounts of practitioners and not field trials.

- One field trial is ongoing at the G.B. Pant University of Agriculture and Technology, but its full results will be available only after five years. According to reliable sources, preliminary observations of these field trials have recorded a yield shortfall of about 30% in ZBNF plots when compared with non-ZBNF plots.

Standing reason on its head

- Third, most of Mr. Palekar’s claims stand agricultural science on its head. Indian soils are poor in organic matter content. About 59% of soils are low in available nitrogen; about 49% are low in available phosphorus; and about 48% are low or medium in available potassium.

- Indian soils are also varyingly deficient in micronutrients, such as zinc, iron, manganese, copper, molybdenum and boron. Micronutrient deficiencies are not just yield-limiting in themselves; they also disallow the full expression of other nutrients in the soil leading to an overall decline in fertility.

- In some regions, soils are saline. In other regions, soils are acidic due to nutrient deficiencies or aluminium, manganese and iron toxicities. In certain other regions, soils are toxic due to heavy metal pollution from industrial and municipal wastes or excessive application of fertilizers and pesticides.

- On their part, agricultural scientists do identify the improper/imbalanced application of fertilizers, that too with no focus on micronutrients, as a matter of concern. Hence, they recommend location-specific solutions to nurture soil health and sustain increases in soil fertility. They suggest soil test-based balanced fertilisation and integrated nutrient management methods combining organic manures (i.e., farm yard manure, compost, crop residues, biofertilizers, green manure) with chemical fertilizers. But ZBNF practitioners appear to insist on one blanket solution for all the problems of Indian soils. One of Mr. Palekar’s favourite remarks is that “soil testing is a conspiracy”.

- Fourth, Mr. Palekar has a totally irrational position on the nutrient requirements of plants. According to him, 98.5% of the nutrients that plants need is obtained from air, water and sunlight; only 1.5% is from the soil.

- All nutrients are present in adequate quantities in all types of soils. However, they are not in a usable form. Jivamrit, Mr. Palekar’s magical concoction, makes these nutrients available to the plants by increasing the population of soil microorganisms. All these are baseless claims. The Jivamrit prescription is essentially the application of 10 kg of cow dung and 10 litres of cow urine per acre per month. For a five-month season, this means 50 kg of cow dung and 50 litres of cow urine. Given nitrogen content of 0.5% in cow dung and 1% in cow urine, this translates to just about 750 g of nitrogen per acre per season. This is totally inadequate considering the nitrogen requirements of Indian soils.

- Finally, the spiritual nature of agriculture that Mr. Palekar posits is troublesome. Some of his statements are odd. He has claimed that because of ZBNF’s spiritual closeness to nature, its practitioners will stop drinking, gambling, lying, eating non-vegetarian food and wasting resources.

- For him, only Indian Vedic philosophy is the “absolute truth”. By placing cows at the centre of ZBNF, he (wrongly) claims that India’s cattle population is falling. From there, he espouses empathy for the activities of gau rakshaks. All of this reeks of a cultural chauvinism that uncritically celebrates indigenous knowledges and reactionary features of the past.

Scientific approach needed

- Undoubtedly, improvement of soil health should be a priority agenda in India’s agricultural policy. We need steps to check wind and water erosion of soils. We need innovative technologies to minimize physical degradation of soils due to waterlogging, flooding and crusting. We need to improve the fertility of saline, acidic, alkaline and toxic soils by reclaiming them.

- We need location-specific interventions towards balanced fertilization and integrated nutrient management.

- While we try to reduce the use of chemical fertilizers in some locations, we should be open to increasing their use in other locations. But such a comprehensive approach requires a strong embrace of scientific temper and a firm rejection of anti-science postures. In this sense, the inclusion of ZBNF into our agricultural policy by the government appears unwise and imprudent.

- In December 2018, NITI Aayog released its ‘Strategy for New India @75’ which defined clear objectives for 2022-23, with an overview of 41 distinct areas.

- In this document, however, the strategy for ‘water resources’ is as insipid and unrealistic as the successive National Water Policies (NWP).

- Effective strategic planning must satisfy three essential requirements. One, acknowledge and analyse past failures; two, suggest realistic and implementable goals; and three, stipulate who will do what, and within what time frame. The ‘strategy’ for water fails on all three counts.

- No new vision

- The document reiterates two failed ideas:

- adopting an integrated river basin management approach, and setting up of river basin organisations (RBOs) for major basins. The integrated management concept has been around for 70 years, but not even one moderate size basin has been managed thus anywhere in the world. And 32 years after the NWP of 1987 recommended RBOs, not a single one has been established for any major basin.

- The water resources regulatory authority is another failed idea. Maharashtra established a water resources regulatory authority in 2005. But far from an improvement in managing resources, water management in Maharashtra has gone from bad to worse. Without analysing why the WRA already established has failed, the recommendation to establish water resources regulatory authorities is inexcusable.

- The strategy document notes that there is a huge gap between irrigation potential created and utilised, and recommends that the Water Ministry draw up an action plan to complete command area development (CAD) works to reduce the gap. Again, a recommendation is made without analysing why CAD works remain incomplete, that too despite having a CAD authority as an integral component of the ministry.

- Goals include providing adequate and safe piped water supply to all citizens and livestock; providing irrigation to all farms; providing water to industries; ensuring continuous and clean flow in the “Ganga and other rivers along with their tributaries”, i.e. in all Indian rivers; assuring long-term sustainability of groundwater; safeguarding proper operation and maintenance of water infrastructure; utilising surface water resources to the full potential of 690 billion cubic metres; improving on-farm water-use efficiency; and ensuring zero discharge of untreated effluents from industrial units. These goals are not just over ambitious, but absurdly unrealistic, particularly for a five-year window. Not even one of these goals has been achieved in any State in the past 72 years. Some goals, such as ‘Har Khet Ko Pani (irrigation to every field)’, are simply not achievable.

Who is accountable?

- A strategy document must specify who will be responsible and accountable for achieving the specific goals, and in what time-frame. Otherwise, no one will accept the responsibility to carry out various tasks, and nothing will get done. Take one goal: “Encourage industries to utilise recycled/treated water”. Merely encouraging someone to do something, is not a “goal”.

- That apart, NITI Aayog does not say who will do this encouraging, and how? Should the State Water Ministries do this by restricting or even withholding recalcitrant industry’s access to fresh water? Should the Environment Ministries cancel clearances for industries which do not practise recycling? Or should the Finance Ministries do this through monetary incentives and disincentives? No one knows.

- Of the issues listed under ‘constraints’, only one, the Easement Act, 1882, which grants groundwater ownership rights to landowners, and has resulted in uncontrolled extractions of groundwater, is actually a constraint. The remaining are are not constraints. These are: irrigation potential created but not being used; poor efficiency of irrigation systems; indiscriminate use of water in agriculture; poor implementation and maintenance of projects; cropping patterns not aligned to agroclimatic zones; subsidised pricing of water; citizens not getting piped water supply; and contamination of groundwater. These are problems, caused by 72 years of mis-governance in the water sector, and remain challenges for the future.

- Ideas listed under ‘way forward’ and ‘suggested reforms’ do not say how any of these will come about. For example, there is no recommendation to amend the Easement Act, or to stop subsidised/free electricity to farmers. On the contrary, the strategy recommends promoting solar pumps. These are environmentally correct and ease the financial burden on electricity supply agencies. However, the free electricity provided by solar units will further encourage unrestricted pumping of groundwater, and will further aggravate the problem of a steady decline of groundwater levels.

Reforms overlooked

- The document fails to identify real constraints.

- For example, it notes that the Ken-Betwa River inter-linking project, the India-Nepal Pancheshwar project, and the Siang project in Northeast India need to be completed.

- A major roadblock in completion of these projects is public interest litigations filed in the National Green Tribunal, the Supreme Court, or in various High Courts. Unless the government has a plan to arrest the blatant misuse of PIL for environmental posturing, not only these but also other infrastructure projects will remain bogged down in court rooms.

- The document takes no cognisance of some real and effective reforms that were once put into motion but later got stalled, such as a National Water Framework law; significant amendments to the Inter-State River Water Disputes Act; and the Dam Safety Bill.

- India’s water problems can be solved with existing knowledge, technology and available funds. But India’s water establishment needs to admit that the strategy pursued so far has not worked. Only then can a realistic vision emerge. It is unfortunate that NITI Aayog has failed to admit this and has prescribed only a continuation of past failed policies. Far from solving our water problems, this helps India to continue walking on the unsustainable path it has pursued for decades.

Download Free PDF – Daily Hindu Editorial Analysis

WhatsApp

WhatsApp